1. How Systemic Problem-Solving Drives Venture Returns

1.1 Introducing Benevolent Disruption

Benevolent Disruption is a new investment concept. It is a practical roadmap to enable improved financial returns by focusing on a minority of companies that are solving fundamental problems for society and the planet.

A ‘Benevolent Disruptor’ is a business that addresses systemic, persistent societal challenges. Examples include (but are not limited to) climate change, healthcare access, financial inclusion, knowledge gaps, or security risks. While most businesses aim to solve a problem of some kind, what distinguishes Benevolent Disruptors is the depth, scale, and relevance of the problem they address.

Not all problems are created equal, and neither are the companies solving them. While companies solving inconsequential inconveniences have raised venture funding (from instant cookie delivery to simultaneous front-and-back smartphone photos), big problems are structural; they stem from persistent challenges affecting billions and shaping our future.

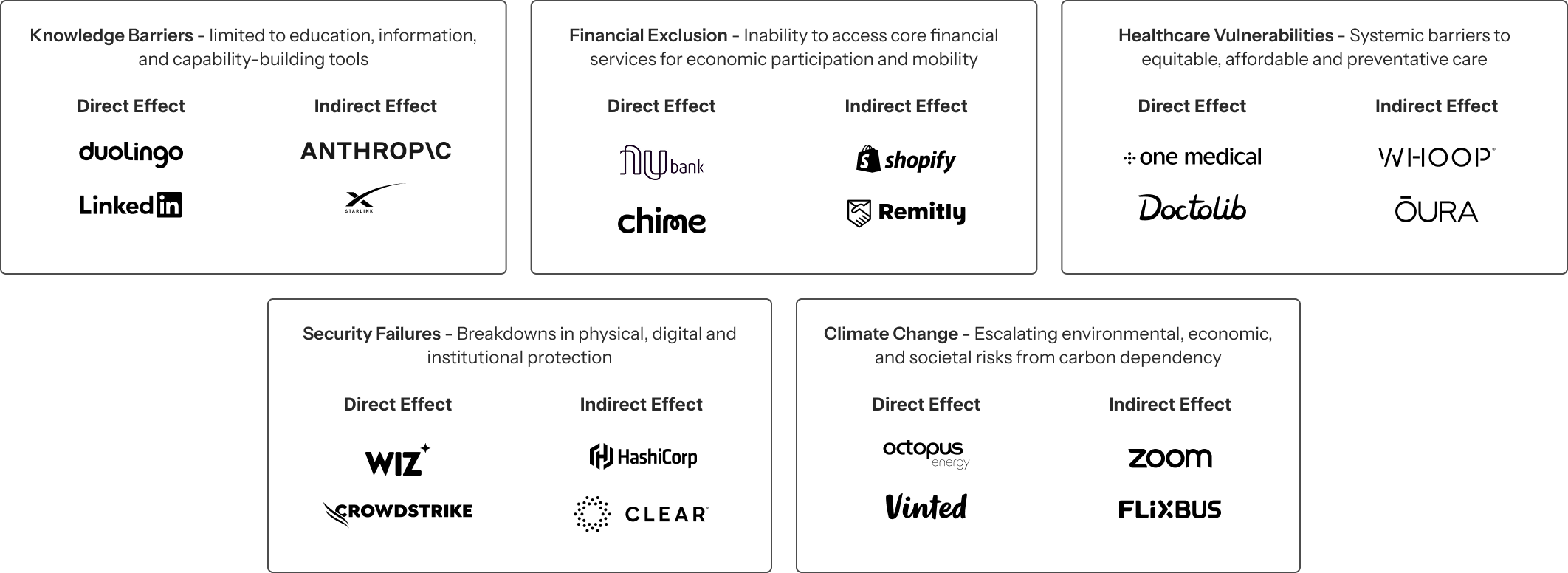

Ask the average bystander, conduct a search online or review the UN’s Development Goals, and five large-scale challenges consistently recur (see Figure 1): knowledge barriers, financial exclusion, healthcare vulnerabilities, security failures, and climate change.

These challenges aren’t inefficiencies at the margins, nor are they abstract development goals like ending poverty or eradicating hunger. Rather, they are venture-scale problems with clear commercial pathways and scalable addressability. They include improving access to essential financial services, digitizing healthcare delivery, accelerating the deployment of renewable energy solutions, expanding participation in the formal economy, and securing digital systems and infrastructure.

Identifying or investing in Benevolent Disruptors begins with first-principles thinking by linking business model incentives to systemic problems (as set out in Figure 1). Some do this directly, generating revenue by solving the problem itself, like Remitly generating profits from global remittances to enable financial access, or Octopus Energy accelerating renewable energy adoption. Others do it indirectly, enabling systemic remediation of these externalities while monetizing elsewhere in the value chain, like Shopify empowering small businesses or Zoom reducing travel emissions by enabling remote work with video-conferencing software.

The paper outlines a clear playbook to spot these companies systematically, and repositions systemic relevance not as a moral signal, but as a recurring driver of superior financial returns.

Figure 1: Benevolent Disruptors: Matching Business Model Incentives to Systemic Problems

Summary: Each bubble shows a major global problem and examples of the Benevolent Disruptors addressing it, grouped by whether their business model addresses it directly (core to profit) or indirectly (as a byproduct).

1.3. Thesis Background: The Paradox of Progress

”"When I invented the web, its trajectory was impossible to imagine… It was to be a tool to empower humanity. Yet in the past decade, instead of embodying these values, the web has instead played a part in eroding them."1

Tim Berners-LeeFounder of the World Wide Web

Historical Context:

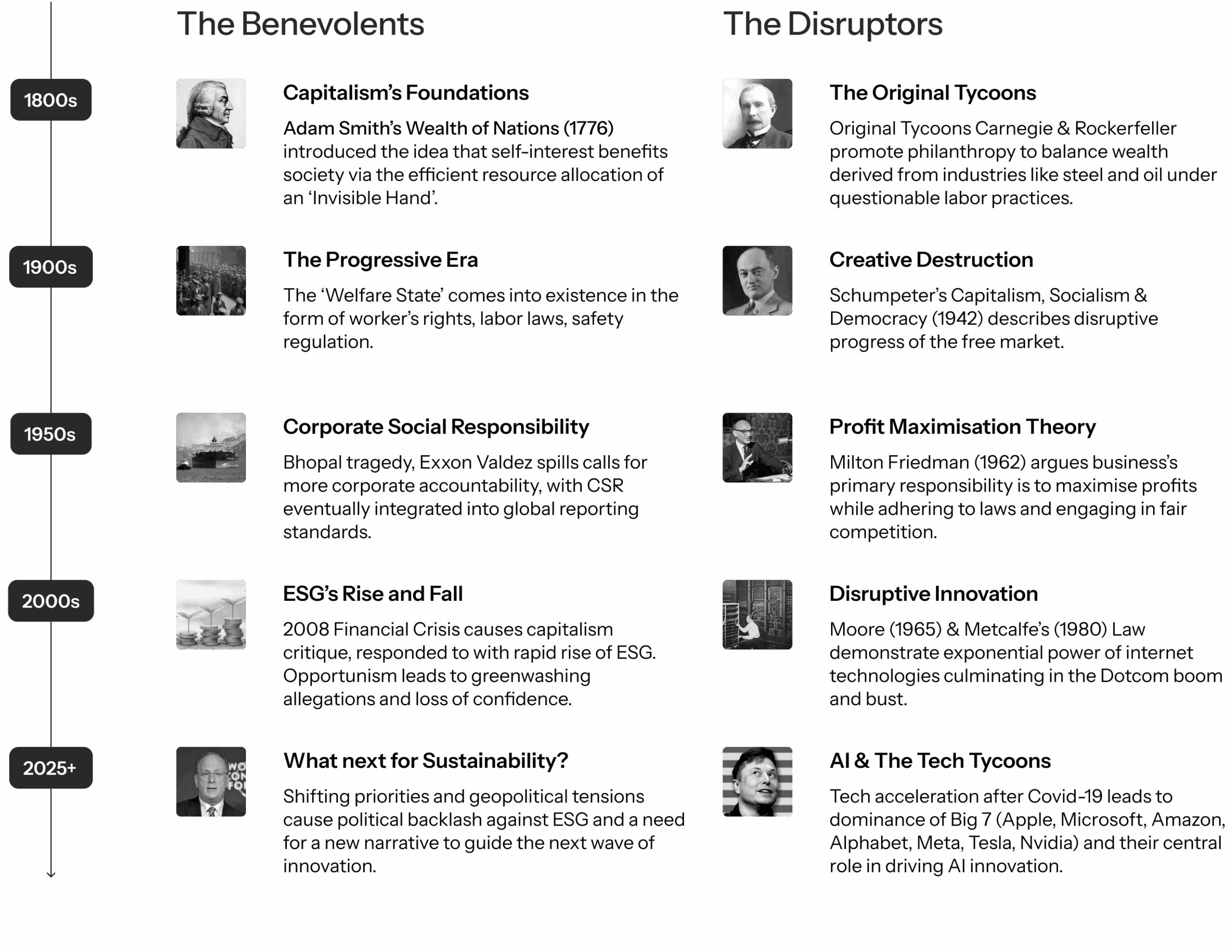

Figure 2: Timeline of Competing Narratives in Modern Capitalism

Capitalism is a tale of competing narratives (Shareholders vs. Stakeholders, Profit vs. Purpose, Private vs. Public) that distract us from a far greater opportunity: What if the greatest economic opportunities of our time lie in solving humanity’s biggest challenges?

For over two centuries, capitalism — and corresponding advances in technology — have been a driving force for human progress. Without capitalism, societies would not have innovations ranging from IVF to indoor plumbing and electricity. Yet, capitalism has also been a system riddled with contradictions and marred by unintended consequences. While market forces have reduced extreme poverty from the long-term average of 79% in 1820 to less than 10% today, these same forces have exacerbated climate risks, widened inequalities, and spurred technological disruptions with profound unintended consequences.2

Consider the industrial revolution, which brought unparalleled economic growth but did so at the cost of inducing a reliance on fossil fuels that now threatens the planet. The digital revolution has similarly transformed human connectivity and productivity while introducing cybercrime, privacy erosion, and amplified social polarization. As a new era of artificial intelligence emerges, technology is transforming knowledge access, while simultaneously raising concerns around surveillance, job displacement, and the concentration of power.

This duality is a structural feature of capitalism, which has long been defined by opposing forces — ‘Shareholders vs. Stakeholders,’ ‘Profit vs. Purpose,’ and ‘Private vs. Public’ — to the extent that the tension between ‘doing good’ and ‘making profit’ often feels irreconcilable. But what if the most significant opportunities of our time lie precisely at the intersection of these competing forces?

Before evaluating this question, it’s worth asking: why has it been missed by capital allocators and innovators alike? The answer lies in the tug-of-war between two legacy worldviews: the ‘Benevolents’ and ‘Disruptors’ (see timeline in Figure 2). Benevolent Disruption transcends these binaries of the past, rejecting both techno-solutionism detached from real needs, and virtue signaling detached from commercial viability. Today’s investment landscape demands a rethink. From geopolitical fragmentation to fragile supply chains and declining trust in institutions, the conditions shaping modern markets have outpaced the logic of legacy playbooks. In response, Benevolent Disruption returns to first principles, solving foundational problems that matter to both business and society. The result is a practical roadmap for capital allocators seeking to back companies that don’t just move fast and break things, but build better systems, unlock real-world value, and outperform in the process.

The most resilient, high-performing companies of the next decade won’t choose sides. They’ll operate at the intersection. These are the fault-lines where value concentrates, and is the essence of Benevolent Disruption: a framework to reconcile this false dichotomy, escape the distraction of competing heuristics, and identify businesses at this intersection of businesses that address the ‘big problems’ affecting humankind while generating extraordinary economic returns.

Amidst the distraction of two persistent but limiting heuristics, this paper lays out four signals for Benevolent Disruptors to factor into their investment frameworks as a mental model for portfolio selection. The result is a new template for capital allocators seeking to back companies that don’t just move fast and break things, but build better systems, unlock real-world value, and outperform in the process.

Why Venture Has Missed the Moment So Far

”"The truth is, the venture business (as a whole) has not risen to the occasion... As an industry, we think our only job is to spawn companies, 'disrupt' markets, deliver strong returns for our LPs and personal wealth for ourselves… and assume society will figure out the rest. This is not the way to build enduring companies or leave a meaningful legacy."3

Hermant TanejaCEO, General Catalyst

Venture capital has long positioned itself as the engine of innovation, but in practice, it has often become a machine for optimizing the familiar: faster, cheaper, slicker versions of what already exists. Over the past two decades, the industry has sometimes drifted toward trend-chasing and hype cycles, funding “feature factories” for Big Tech while systematically underfunding the foundational systems that underpin resilient economies. Rather than tackling climate resilience, healthcare infrastructure, or education access, the industry has often been distracted by convenience apps and incremental software plays. Even in high-impact areas such as clean energy or biotech, private capital often follows only after public or philanthropic capital has absorbed early-stage risk.

While venture capital has generated significant financial returns and driven technological progress, its current heuristics — focused on speed, simplicity, and rapid exits — are not well-suited to identifying or supporting businesses solving long-term structural problems. The result is an innovation pipeline that underrepresents some of the highest-leverage opportunities across both societal and financial dimensions.

Why Current Frameworks Have Failed

The universe of businesses driving positive change and the frameworks that seek to capture them do not match. What began as an effort to align capital with people and planet has fractured into a patchwork of ESG ratings, disclosure criteria, and impact classifications. These frameworks were designed to formalize responsible investing. Instead, they have often produced confusion and constraints. The same company might be rated a sustainability leader by one agency and a laggard by another, depending on which data is selected, how it is weighted and when. Arms manufacturers, for example, may be included or excluded depending on the geopolitical context.

Similarly, companies with strong governance structures but limited or even negative societal impact can still earn top ESG scores. These contradictions have created what many now refer to as the ESG standoff : a market dynamic where the appearance of sustainability often matters more than actual effectiveness. In addition, greenwashing — the practice of overstating or misrepresenting environmental or social impact — is a valid and growing concern. The problem lies not just in corporate intent, but in how rigid frameworks in fact make greenwashing easier to perform and harder to detect. When compliance with labels or checklists becomes the goal, companies are incentivized to optimize for perception over performance. Impact is often measured in disclosures and ratings, rather than in real-world outcomes.

This misalignment has led to a distorted investment landscape. Capital flows toward companies that conform to frameworks, regardless of whether they generate meaningful real-world impact. Businesses that score well on ESG metrics or fit neatly into sustainability classifications often trade at a premium not because they are solving systemic problems, but because they check the right boxes. This has introduced what many describe as the “sustainability premium”: higher entry prices, limited scalability, and a narrower universe of investable opportunities. At the same time, companies delivering tangible solutions to foundational challenges are frequently overlooked or excluded, simply because they do not fit the frame.

Efforts to bring structure through regulation, such as the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), have added clarity in some areas but also reinforced rigidity. Fund managers are increasingly forced to allocate based on classification thresholds rather than investment insight.

Further, ESG has become increasingly politicized. The public discourse and debate has been targeted by all sides of the political spectrum with some urging that it infringes too far in capitalist processes, with others arguing it doesn’t go far enough. The politicization has mainly served to reduce confidence and disincentivize investors from interacting with the process. Investors are increasingly concerned by the potential political backlash they may be subjugated to from all sides in this space. As a result, they have often chosen the path of least resistance: doing nothing, or abandoning the premise entirely.

In sum, the current frameworks are often not fit for purpose. This is because they do not accurately or effectively capture the universe of businesses they intended to: those driving positive change.

1.4. Benevolent Disruption in Context

Instead of relying on labels and titles, Benevolent Disruption prioritizes the one thing capital should ultimately measure: outcomes.

This paper’s logic restores common sense to asset allocation. Companies that affect meaningful, transformative change at scale are more likely to outperform in the long run. The size and complexity of a company’s challenge are signals, not barriers. This way we foreground common sense, a principle too often lost when investors feel they must follow perception and buzzwords.

Take, for example, a cybersecurity firm protecting critical infrastructure. By typical ESG measures, it might not be seen as green. But the firm would drive climate resilience, a quality that applying a lens of Benevolent Disruption would identify.

That’s because this paper proposes a fundamentally different logic: that companies solving meaningful problems at scale are best positioned to outperform. It treats the size and complexity of a challenge as a signal, not a barrier. And it offers a practical way to identify winners in spaces others tend to ignore, whether passed over by venture capital, or left out of ESG frameworks because their impact isn’t immediately obvious. Yet this, as with a cybersecurity firm or video conferencing innovator, is exactly where some of the most durable and mispriced opportunities are emerging.

This common sense approach restores space for investment discretion, a fundamental quality that our current system of labels and regulatory hoops surpasses. This emphasis on an investor’s agency is encoded in the roots of “benevolent”, derived as it is from bene (good) and velle (to will); the role of the investor is not to comply with a checklist, but with intent and foundational principles to build a portfolio that delivers both social and financial value.

Try another example: a company improving data center efficiency. It may not qualify as sustainable, even though it enables the energy transition at scale. That is why investing at the frontier of systemic change requires room for judgment.

This stance is not a moral one. It is a practical lens for surfacing high-conviction opportunities that conventional models miss. It enables investors to move beyond decisions driven by templates and branding toward an investment logic better suited to identifying the problems, and delivering the returns, that will define the next economy.

If allocators care about impact, they should underwrite it the way they underwrite financial performance: by evaluating what companies actually deliver. If a company does not perform financially, it will not exist long enough or grow large enough to achieve impact at scale. Without grants or subsidies, financial success must be achieved for a company to drive the impact it desires. If they trust the approach, they allocate. If not, they don’t. In either case, market discipline — not box-checking — leads.

1 Berners-Lee, Tim. “Marking the Web’s 35th Birthday: An Open Letter.” Medium, March 12, 2024. Available at: https://medium.com/@timberners_lee/marking-the-webs-35th-birthday-an-open-letter-ebb410cc7d42

2 Roser, Max. The Short History of Global Living Conditions and Why It Matters That We Know It. Our World in Data, 2016. Last updated 2024. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/a-history-of-global-living-conditions

3 Taneja, Hermant. “Hermant’s Year-End Letter to LPs,” General Catalyst, December 20, 2022. Available at: https://www.generalcatalyst.com/stories/hemants-year-end-letter-to-lps