3.1. They Prioritize Over Optics

The strongest companies don’t always say the right things, but they always do the right things. In a landscape saturated with ESG ratings, sustainability frameworks, and impact metrics, true value lies in outcomes, not branding.

Fund managers are often encouraged, explicitly or implicitly, to prioritize companies that fit into familiar categories, for example those which report against key ESG metrics, use the right language in their disclosures, and present a recognizable impact narrative. Yet this focus on external alignment can distort the investment process, diverting capital towards businesses that look socially responsible on paper, while overlooking those that deliver real system-level change.

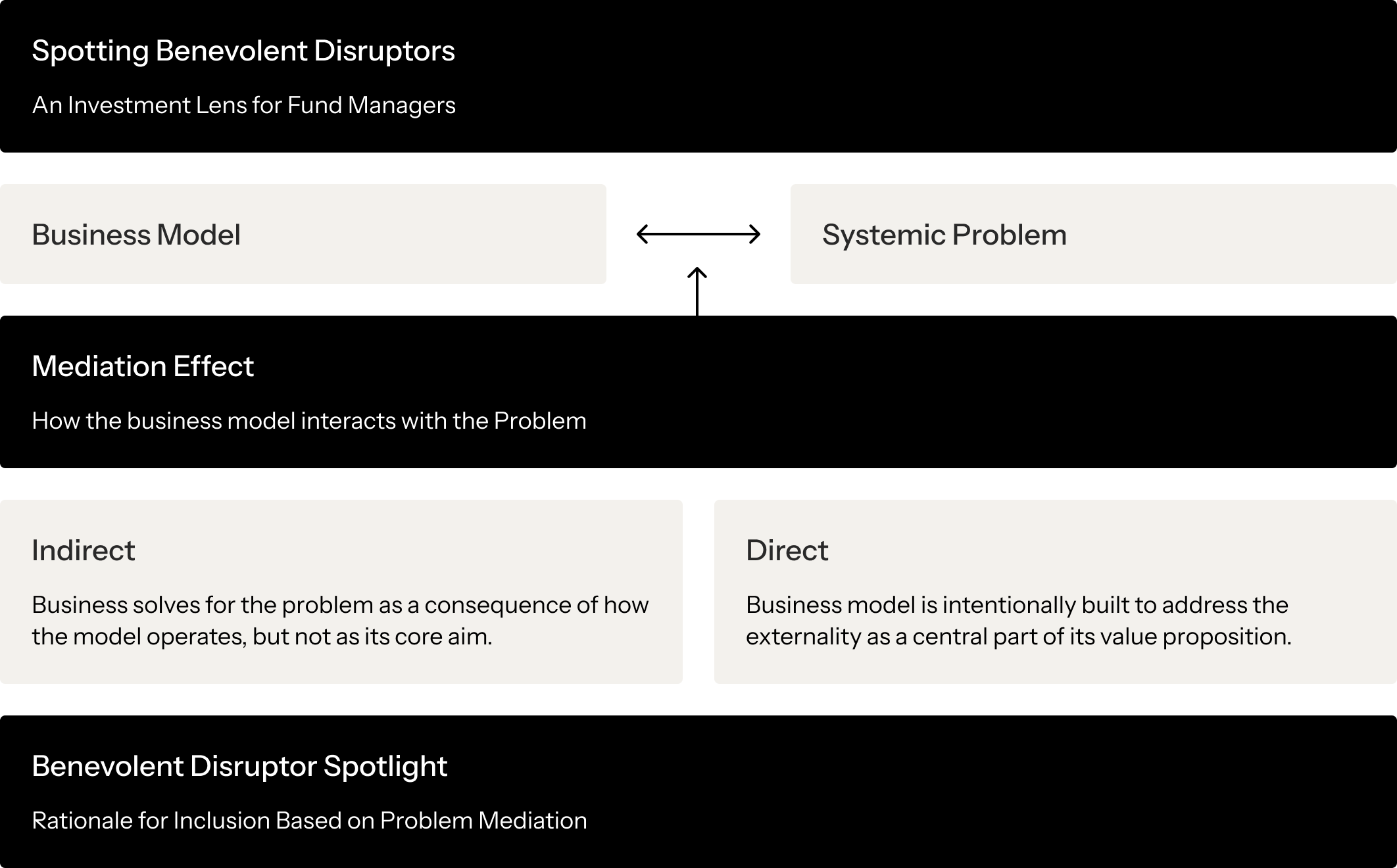

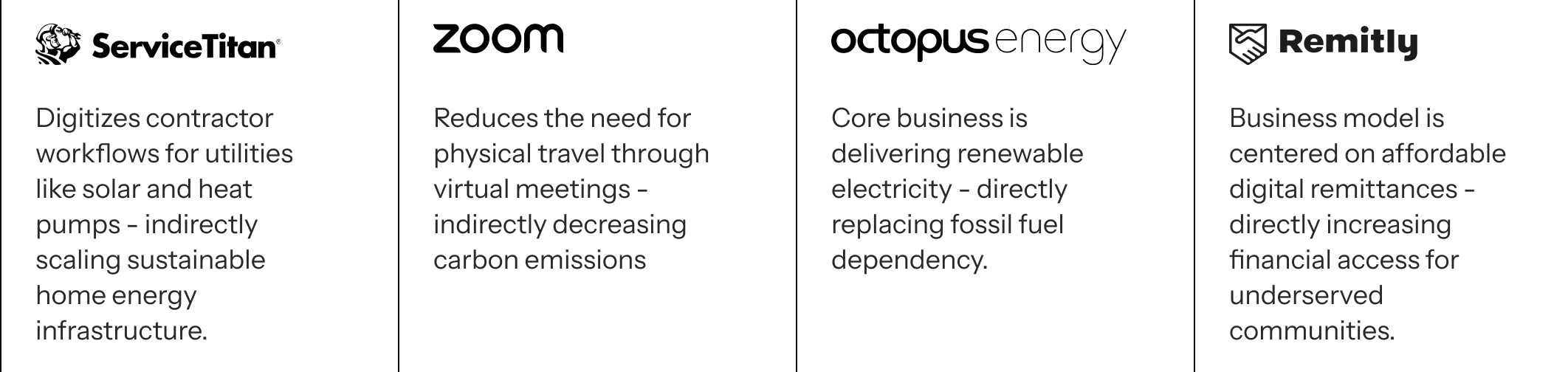

Many of the businesses solving the most pressing global problems fall outside traditional ESG screens and impact narratives. They may not identify as climate or social enterprises, yet often they address negative externalities more profoundly than those that do. Their impact is embedded in the structure of their business model, not in how that model is packaged. By focusing on output, not input, Benevolent Disruption includes businesses that may solve problems — but not deliberately. Understanding this mediation effect (direct or indirect) between a business model and the externality opens up a new genre of opportunities that have long been overlooked.

Crucially, the data supports this approach. Indirect Benevolent Disruptors — those companies whose positive impact emerges not through direct positioning or as their core driver of revenue, but through the structure of their operations — generate 67% higher returns than traditional VC investments. These outsized returns are not a function of storytelling, but of real business model advantage.

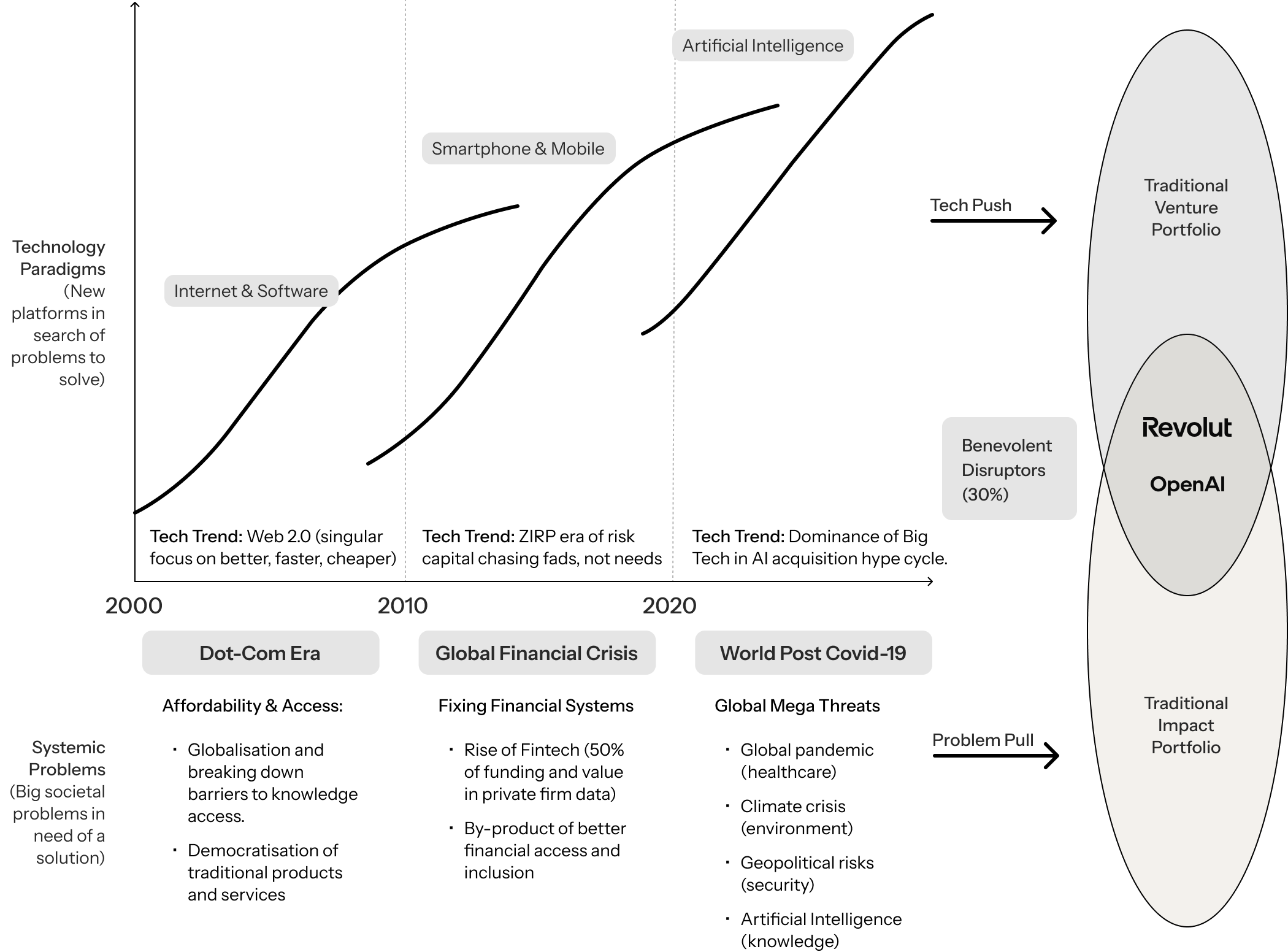

Figure 13: Investment choice is critical in rationalizing portfolio selection. A First Principles or ‘Common Sense’ Approach to selecting Benevolent Disruptors into Fund Portfolios

Summary: Fund managers can surface overlooked upside by analyzing how a company’s business model mediates systemic problems – either directly or indirectly. The key is understanding whether the externality is solved as a core function of the business or as a consequence of its design. In a landscape dominated by rigid impact and ESG frameworks, discerning investors focus on structural relevance and problem-solving potential, using discretion to surface outsized value that others overlook.

The most viable businesses solving societal problems are not always the most visibly ESG-aligned. By focusing solely on the impact outcome, and ignoring all other metrics, a more accurate picture of those businesses driving positive change comes into view. Reconsidering what qualifies as a business driving systemic change is necessary. This requires applying logic rather than relying solely on sector, taxonomy, or label (section 2.ii Methodology). A company does not need to explicitly define itself as “impact” to have significant, measurable effects on the climate, on equity, or on access.

Consider Zoom. It is rarely mentioned in the context of sustainability and would almost certainly fall outside the scope of any impact or climate fund. Yet, by enabling remote work at scale, it helped reduce global business travel and aviation emissions during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. The change it enabled — how organizations work, how people commute, how infrastructure is used — has had a substantial indirect impact on energy use and emissions. Zoom is not a climate company by branding, but its operating model has generated clear climate.

Recognizing When Optics Hide Structural Weakness

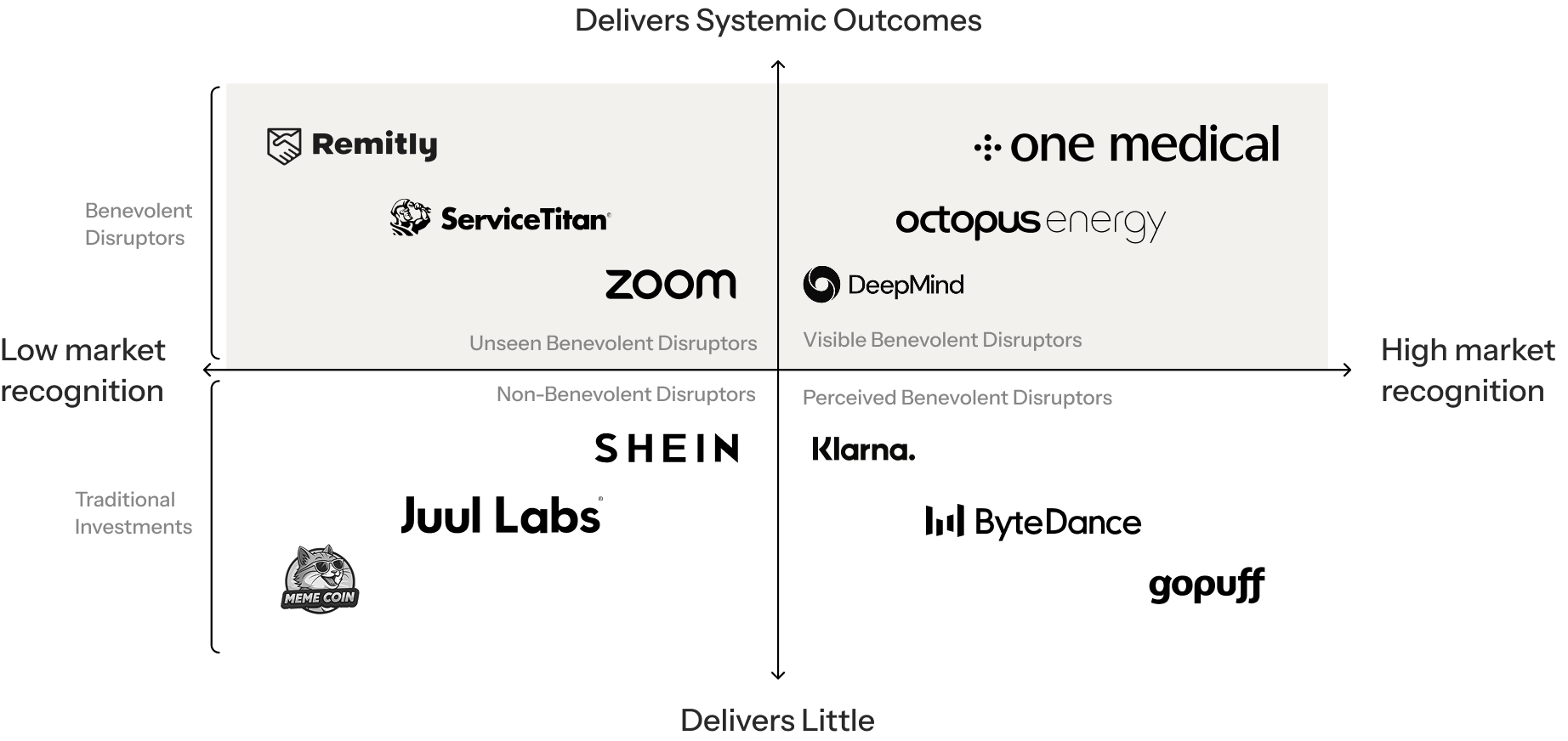

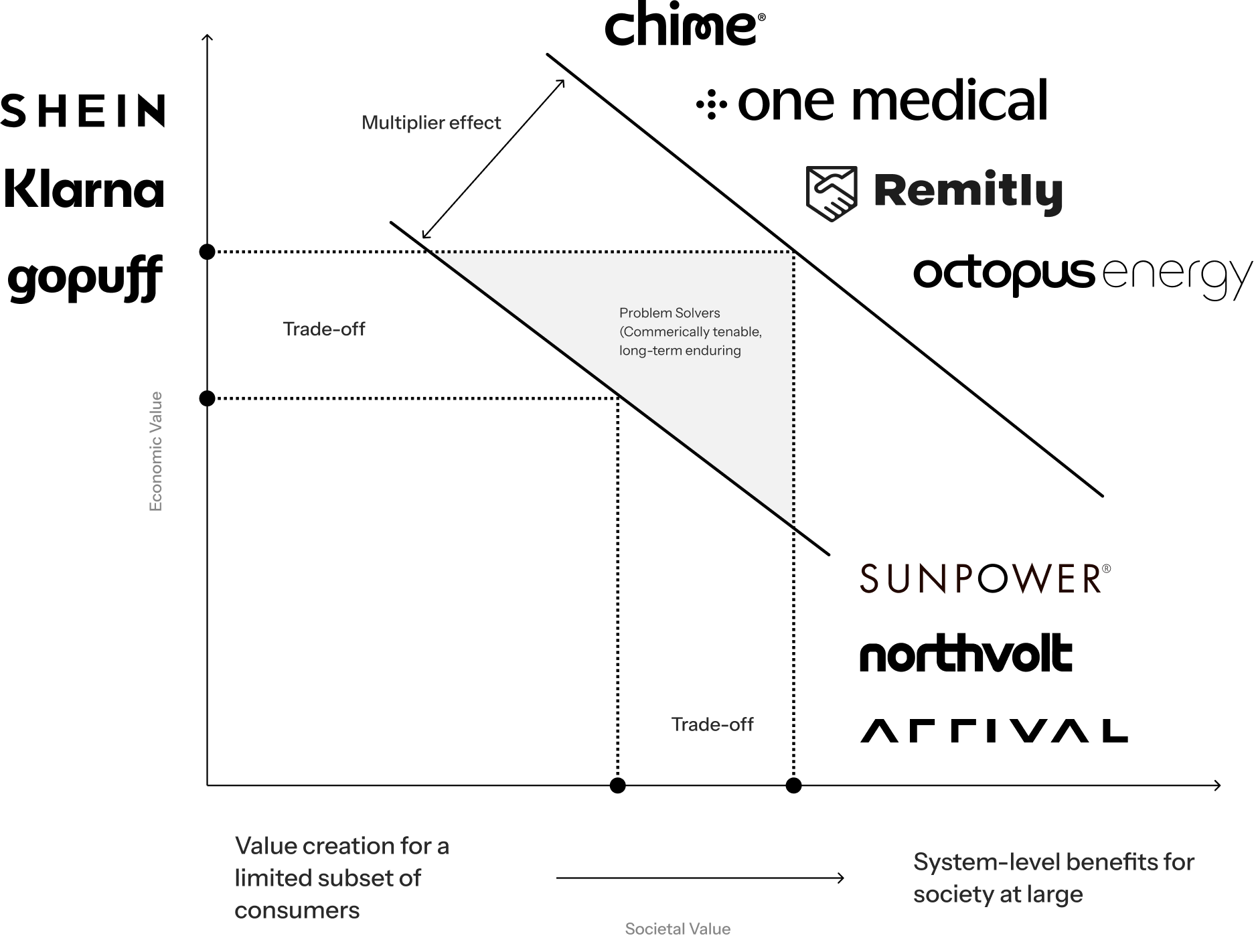

Second, optics can mask deeper business model weaknesses, and, in some cases, even accelerate them. The most visible ESG businesses are not always the most viable. High-impact branding can create the illusion of strong fundamentals, even when a company’s business model is fragile underneath. When capital is allocated based on ESG visibility or narrative fit, rather than actual performance, it can push companies to raise at inflated valuations and scale before they’ve proven they can do so efficiently or sustainably. That’s the risk behind the “sustainability premium” — when demand for labeled impact assets drives prices higher, regardless of whether the fundamentals justify it. In the short term, these companies may be celebrated. In the long term, many struggle to meet expectations.

Northvolt offers a telling example. The much-celebrated Swedish battery manufacturer that aimed to accelerate the electric vehicle transition and became a public exemplar of sustainable innovation, along with others like Arrival and SunPower. On paper, it was everything an ESG-aligned investor could want. In practice, it lacked the capital efficiency, scalability, and operational resilience needed to build a long-term business. The company’s recent bankruptcy underscores a painful lesson. The product was needed, the mission was aligned, but the underlying business model did not hold. Its failure illustrates that solving a big problem is not enough if the business cannot do so at scale, with efficiency and endurance.

Viewed alongside Zoom, Northvolt highlights the disconnect between surface-level alignment and deep structural impact. The former received capital and acclaim but ultimately collapsed. The latter lacked ESG visibility yet has had broad systemic influence and continues to deliver strong financial performance. The comparison underscores a crucial point for fund managers: impact is not always where they are told to look. The most investable companies are not necessarily those with the strongest sustainability narrative, but those whose operations, by design, contribute to real-world outcomes.

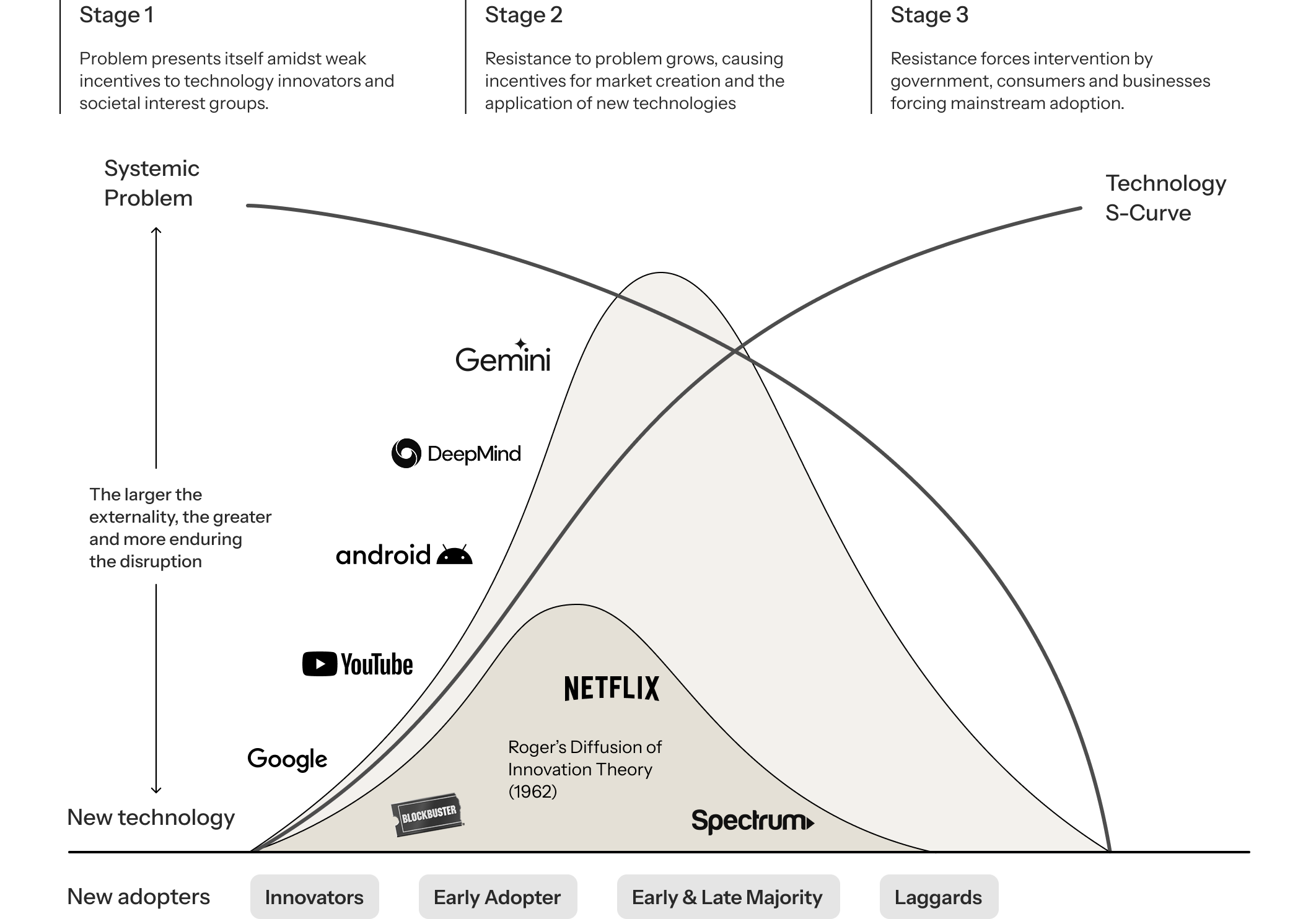

Figure 14: The Benevolent Disruptor Spectrum: Hidden Value Beyond the Obvious

Summary: In a market driven by optics, Benevolent Disruptors distinguish themselves through outcomes. They create the value where it’s least obvious: by embedding solutions into scalable business models rather than signalling intent. This framework helps distinguish companies delivering real systemic outcomes from those simply optimized to look like they are.

For capital allocators, the challenge is not simply to filter for intent or optics, but to assess whether a business is solving a meaningful problem in a way that is financially viable, operationally scalable, and structurally resilient. This is why Benevolent Disruption insists on intentionality over prescription. By empowering fund managers to lead rather than follow, it allows them to find value where others are not looking among the indirect, under-the-radar Benevolent Disruptors that are structurally built to scale.

Case Studies:

Indirect Benevolent Disruptor: Remitly

For years, financial institutions have marketed inclusion while keeping high fees, slow transfers, and exclusionary policies intact. Financial access was treated as a CSR initiative – and not a business priority. Remitly proved otherwise, redesigning remittances through business model innovation to make financial inclusion faster, more secure, and more affordable. By expanding accessibility, it unlocked an overlooked market, turning financial inclusion into a powerful engine of growth. In 2024, Remitly processed $54.6B in remittances, expanded to 7.8M customers, and generated $1.3B in revenue. Its growth was not driven by positioning, but by operational design that expands insurance access to millions of underserved customers.

”"At Remitly, we’re relentlessly focused on making the cost of sending money internationally fair and transparent, because every dollar saved is a dollar that stays in the hands of the families who need it most. Our capital-efficient model, built on trust and a per-transaction approach, ensures that as we grow, our customers benefit. We’ve shown that real impact isn’t at odds with financial success — it fuels it”

Matt OppenheimerFounder, Remitly

Direct Benevolent Disruptor: Marshmallow

Insurers have long framed fairness as a trade-off, arguing that inclusion in risk pricing comes at the expense of financial viability. Many embraced performative ESG commitments, marketing diversity and equity while leaving exclusionary underwriting untouched. Marshmallow flipped the script. By integrating AI-driven underwriting and alternative data, Marshmallow assessed drivers based on real-world driving behavior, not blunt proxies like nationality or credit history. This shift didn’t just improve underwriting accuracy; it expanded access and unlocked a vast, underserved market. In 2023, Marshmallow grew revenue by 98% year over year, reaching more than $300M. Its success wasn’t driven by messaging – it was driven by model design. In a sector known for rebranding old models under new labels, Marshmallow exemplifies how outcomes not optics, are what drive financial returns.

”"The best businesses solve systemic problems at scale. By rethinking outdated risk models, we’ve built a fairer, faster, and more scalable insurance model that proves financial inclusion and profitability go hand-in-hand”

Oliver Kent-BrahamCo-founder & Co-CEO, Marshmallow Insurance

Key takeaway for capital allocators:

The most investable companies are not always the most visible, and the most visible are not always the most viable. The companies solving meaningful problems at scale often operate without ESG labels or polished narratives. Breakingfrom optics and frameworks and focusing only on whether the business model solves the negative externality, opens up a new genre of ‘Indirect Benevolent Disruptors’. Benevolent Disruption focuses on businesses that embed real impact into their business model by output, not declaration. For fund managers seeking differentiated returns and real-world impact, the challenge is not to follow narratives, but to investigate structures; to look past the surface and identify the quiet operators who are, in practice, building a more resilient system.